|

Girandoni air rifles and Girandoni style air guns - A major research study. Keywords: Lewis and Clark, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Lewis and Clark Air Rifle, Lukens, Beeman Girandoni, Girardoni, Gilardoni, Girandony, G, Air Gun, Airgun, Military, Repeater, Repeating, Rodney, Expedition, Sioux, Brunot Island, Voyage of Discovery, Corps of Discovery, Cowan, Keller, Carrick, Currie, Baker, Baer, Hummelberger, Eichstädt, Stewart. Austrian Large Bore Airguns Girandoni style air rifles and pistols - preliminary research presentation.

. By Robert D. Beeman Ph.D.[1]

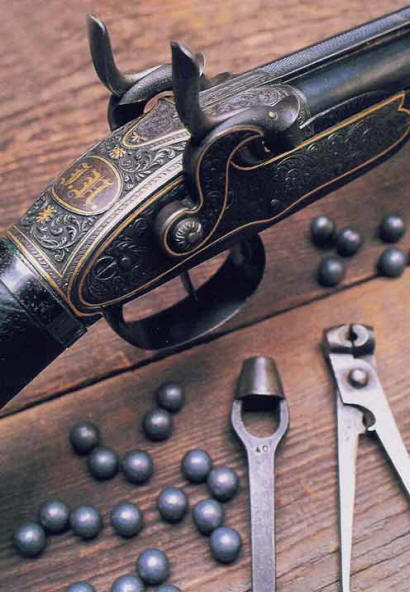

For the VERY latest information concerning amazing new discoveries about the Lewis and Clark airgun, please click on: the Lewis Assault Rifle section AND see the latest notes in the What's New section of this website. URGENT REQUEST: We are very anxious to obtain, or learn of a possible source for, a portrait of Bartholomäus Girandoni (1744-1799) and/or his son Johann. Please relay any clues to DrAirgun@Beemans.net. Large bore antique airguns (Windbüchsen) have always been a specialty of the Beeman Airgun Collection. In the last three decades, Mrs. Beeman and I have been fortunate to acquire one of the largest collections of Austrian large bore airguns and information about them. This is a preliminary presentation about some specimens from that, starting with the best known of these arms: the famous Girandoni system airguns first developed slightly before the 19th century. The eventual demise of these military airguns by about 1810 had little to do with their effectiveness, but was more involved with the logistics of keeping them charged in combat, the inability of contemporary gunsmiths to maintain the guns, and with the political implications of such weapons which mistakenly were believed to be "silent". That the design was widely copied later in civilian circles indicates that it was well accepted by discriminating civilian gunsmiths and shooters and that such guns really were effective hunting arms. The system really was more suited to hunters who do not fire so many shots as a soldier, who can have the air reservoirs pumped up at leisure - even by a servant, and whose lives generally do not depend on the gun. Virtually all of the 19th century copies of the Girandoni system airguns proudly bear the name of the maker and the city of his shop. Truly outstanding copies, sometimes richly ornamented with gold and silver coatings and inlays, deeply engraved, and bearing superb, ornate stocks bear the names of such makers as Contriner, Lowentz, Fisher, etc.. Lowentz and Schembor of Vienna and Staudenmayer, Fisher, and Mortimer of London who produced a very few high quality Girandoni system repeaters and even single shot air rifles and shotguns with the characteristic Girandoni styling. There are other makers of lesser rank and quality. Copies made after 1900 generally are unsigned and some are crude, even clumsy. As noted by Ernest Cowan, the Girandoni system is not easy to reproduce in high quality. After some detailed coverage of the Girandoni military repeating air rifle, we will consider the Girandoni repeating air pistol, several Girandoni system airguns and Girandoni style airguns in the Beeman Airgun Collection and some of the myths about the Girandoni system guns. They following material is only a preliminary posting of our current study. The most intense research is now concentrated on the Girandoni repeating air rifles, especially on the recent work and study of Colin Currie, Geoffrey Baker, Ernest Cowan, Richard Keller, and Robert Beeman. The next phase will concentrate on the Girandoni system airguns and Girandoni style air guns. One of the major research objectives is to greatly increase the knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of these special airguns. We constantly are seeking additional specimens, references, and information so that we may present the best source of information on this group. A few examples of Girandoni and Girandoni-system airguns from our collection are shown in this article. Material on other such specimens in the Beeman Airgun Collection will be added as we have time for their study, photography, and addition to our website. We VERY MUCH welcome information on other Girandoni system airguns and are always on the market to buy additional specimens for inclusion in our upcoming book which finally will tie the existing specimens together into a permanent legacy for this gun-making genius - a collection which is destined to be maintained as a unit in an appropriate international arms museum - rather than being sold and thus scattered into obscurity over the globe.

What is our background in this area of study? Mrs. Beeman and I have been intensely interested in antique large bore

airguns, especially the Girandoni system rifles and pistols, for over three

decades. This began long before our interest in collecting and studying airguns

of the 20th century. During that time we have studied such airguns with the late

Henry Stewart (who started us on the trail to the Lewis airgun) in his

astonishing gunroom, and in person in the collections at the Tower of

London, Beeman Airgun Collection, Virginia Military Institute, Smithsonian

Institute, U.S. National Firearms Museum, U.S. Army War College, Fort Clatsop Museum, German National

Museum, Military Museum of Turkey, Kopenhagen Tøjhusmuseum (Royal Danish Arsenal

Museum), Milwaukee Public Museum, Zurich Landmuseum, Bern Historical Museum,

Solthurn Zueghaus, Deutsch Jagdmuseum - Munich, Jagdmuseum Kranichstein -

Darmstadt, Waffensammmlung des Kunsthistorischen Museum and

Heeresgeschichtliches Museum – Wien, Staatliches Museum – Schwerin, Victoria and

Albert Museum – London, and several other important gun collections throughout

the world.. The Jagdmuseum Kranichstein in

Darmstadt, Germany and the

Heeresgeschichtliches Museum in Vienna, Austria were especially valuable in our

quest for information on this design. In most cases, Mrs. Beeman and I were allowed to

work in the private research facilities of the museums, in discussion with and

active participation of the arms curators, studying, photographing, and even

disassembling these incredible arms. In addition, we have studied airguns at

innumerable gun and airgun shows in

America and overseas and we carry on a long and vigorous exchange of information

with other museums and leading collectors all over the world. We are enormously

fortunate to have been able to develop the Beeman Airgun

Collection. A great deal of

study has been done in that collection, which includes several models of the

Girandoni design. Antique large bore airguns are the main

emphasis of the Collection, apparently the world’s largest such collection. The Girandoni Repeating Air Rifle Presented here is information which finally develops a fairly clear picture of the features and history of the Girandoni military repeating air rifle. This information has become especially interesting and relevant because so much of it is new. The operation and special features of this gun, even its shortcomings, may be even more important to us than its fabled firepower. After inventing an ingenious, but unreliable and unsafe, multiple feed system for powder burning firearms in the very late 1700s, Bartholomäus Girandoni (also spelled Girandony, Girardoni, etc.) of Vienna (originally from Ampesso in the Southern Tyrolean Alps) very successfully adapted the system to large bore airguns. Most of the following details are from the wonderful presentation of the design and details of this gun recently published by the British gun researchers Geoffrey Baker and Colin Currie (2002, 2006) and the meticulous and precise physical research of Ernie Cowan and Rick Keller, both combined with research and analysis by Robert Beeman. The Girandoni system was adopted, in great secrecy, as the Austrian military repeating air rifle (Hummelberger and Scharer, 1964/65). It has been recorded that the system was invented in 1779 or 1780, but deliveries of these guns to the Austrian army did not begin until between 1787 and 1791. Hoff’s (1977) classic reference on antique airguns and Hummelberger and Scharer (1964/65) indicate that about 1500 Girandoni military airguns were produced and that finally they were retired from service to Olmütz in Bohemia in 1815. Specimens with suggested, but unsupported, dates as early as 1797, and similar versions, but more advanced than the military models, are known from Joseph Lowenz and Joseph Contriner in Vienna. Hoff indicates that other Viennese gunmakers started making most of their copies of the Girandoni system well after the Austrian Army had given up all interest in such guns in 1815. Samuel Staudenmayer also began to make modified, surely very expensive, versions of these guns in his London shop from about 1806 to 1832.

Fig.2. Left

side, loading block protruding in resting position. Note

especially the junction between the iron air reservoir and the

brass receiver. Corrupted or non-original copies may display

significant differences at this point.©2002,

Robert David Beeman

Fig. 2a. Air reservoir cap (left image). This brass piece is screwed into the forward end of the iron air reservoir. The air valve assembly is threaded onto the back side of this brass plate. The cap with attached valve assembly is removed by twisting w/ the cap removal key at the right. Beeman Girandoni original cap and photo. Key made by E. Cowan, 2004.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 3. The combination air intake/exhaust valve and valve housing from the front of a Girandoni air reservoir. The housing is threaded to the rear of the air reservoir cap (above). Such valves, with a single coil spring around a valve spindle with a valve seat at the forward end, were common in butt reservoir guns for at least one hundred years prior to the Girandoni airgun. The actual Girandoni airguns are unusual in having a coil spring made of brass – very advanced for the period and difficult to make, but necessary because moisture from air condensation would rust an iron or steel spring.. The three parts at the left are from the Beeman Girandoni airgun; the three parts on the right were made by Ernie Cowan in 2004 for a museum copy of this gun. Beeman collection and photo.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 4. The Girandoni system - upper two images show tubular ball magazine on right side of gun, distinctive loading block traversing the receiver. Note that receiver casting is a single top piece. Again notice the smooth transition in lines between the receiver and the air reservoir in this authentic specimen. Lower image shows the sliding loading bar with its ball socket and with the right hand retaining screw removed. These loading bars were tapered so precisely that, before the magazine spring was added during reassembly, the bar would slide into an airtight battery position by its own weight! Caution: due to camera angle and the level of the ruler relative to parts, measurements from such photos may be only approximate. Beeman collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig.5. Ramrods/Cleaning Rod Tips. Top image - Beeman Girandoni, rod may be an early replacement. Lower - museum copy of ebony rod with bone tip cleaning rod for museum copy Girandoni military repeating rifle. Note that in breech-loading airguns, the only function of the rod was for bore cleaning and pushing back stuck balls, not for ramming. Steel rods are NOT original; guns with steel rods should be examined for damage to the delicate, shallow (only 0.005") rifling. Upper rod from Beeman Collection. Lower rod by Ernie Cowan. Photo by R. Beeman.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 7 Inside view of the Beeman Girandoni’s lock, without mainspring. Note the tumbler and sear in full-cock position. The bridle at upper right holds these parts in their proper relationship. (Unless otherwise noted, all scales in this report are metric, marked in millimeters.) Beeman collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 8. Beeman Girandoni repeating air rifle with lock plate removed. Note that only the upper part of the one piece receiver is solid cast metal. Stock wood and the separate trigger guard form the bottom half of the receiver a potentially weak area of the original Girandoni design. The brass Beeman Museum disc is 7/8" (22 mm) in diameter. Beeman collection.©2002, Robert David Beeman

Figure 9. Original receiver of the Beeman Girandoni military repeating airgun. Only the separate trigger guard parts, and stock wood to be added later, form the bottom half of the receiver. Note the tiny bit of lower lock plate support ledge, at the far left side of the receiver cavity, which allows easy alignment and assembly of the lockplate into the finished gun. This “little notch” is diagnostic of the airguns which followed the original Girandoni design in the decades following its introduction – it appears on several Girandoni style single shot and repeating air rifles and shotguns, even a repeating air pistol, in the Beeman Collection. Beeman collection and photo.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 10.. Above receiver - bottom view.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 11. Reproducing the receiver for a museum copy. First, the actual receiver must have a plastic casting (top two images) made by making a flexible mold around the receiver, removing the receiver and then adding a special fluid to the mold cavity which expands, as it hardens, to the same degree as the later molten brass will shrink as it cools. A rammed sand mold is made around this plastic casting, with a separation line. The plastic casting is removed and the rammed sand mold filled with molten brass. The resulting brass casting (3rd and 4th images) is removed after cooling and then roughly machined to shape (bottom image- note fin for clamping while working the piece. It will be ground off as one of the last steps.). Beeman photos of work by Ernie Cowan.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig.12.Rear surface of the receiver of the Beeman Girandoni military air rifle. The bean-shaped black area above the steel striker pin sleeve is the entrance to the air passage which was drilled and filed into the solid metal casting when the gun was made. The valve body of the air reservoir screws onto the threaded shaft presented here. Beeman collection and photo.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 13.. Rough shaping of the brass casting of the receiver, rear view, showing the start of the air passage and hole for striker pin sleeve. Again, note the temporary clamping lug on top. Beeman photo of work by Ernie Cowan.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 14. Receiver of a replica Girandoni military repeating airgun- done to original scale and specifications. Note that the air channel from the rear of this unit to the threaded barrel socket on the front is a curved tunnel cast into the upper part of the receiver; Cutting this channel takes a lot of careful hand work. Only the separate trigger guard parts, and stock wood, to be added later, form the bottom half of the receiver. (The striker latch assembly is black and the latch spring is silver-colored. Striker latch guide screw has not yet been added.) Photo courtesy of G. Baker and C. Currie.

Figure 14.1. Butt reservoir of the original Beeman Girandoni air rifle. Look very carefully to see the marks of the rivets above the seam line about the middle of the reservoir. Ruler marked for 6 inches and 15 cm. Evidently all authentic, original air reservoirs for the Girandoni military repeating air rifle were made WITHOUT a leather cover. This is consistent with such reservoirs being charged at central pumping stations while largely submerged in water. Soldiers issued Girandoni air rifles would receive at least one slip-on leather cover for use in cold weather. Beeman collection and photo.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 14.2. Cap and heavy iron sheet shaped for museum copy of Beeman Girandoni air reservoir. Beeman photo of work by Ernie Cown.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 14.3. Forward part of Cowan museum copy air reservoir riveted to secure seam. Cap cup and seam will be brazed to seal them. These authentic original details and special brazing certainly will not be present or done by the original methods in most copies which will be made by others. Beeman photo of work by Ernie Cowan. .©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 14.4. Rear thimble of original Beeman Girandoni and sand casting made for the Cowan museum copy of same. The casting will require a great deal of hand work and finishing. Note again the poor metal to wood fitting of the original Girandoni airgun. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Figure 14.5. All of the parts, except for the butt air reservoir, during construction of museum copy #4 of the Beeman Girandoni by master craftsman Ernie Cowan for Robert Beeman. Magazine tube and loading block are in place. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

*-------

Figure 15.

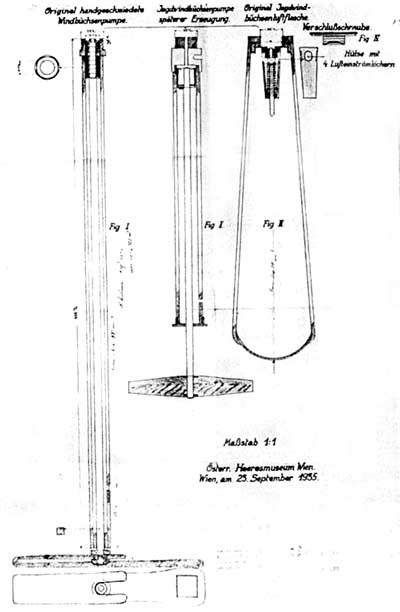

Fig. 16. Head of the air pump from authentic museum copy of the Girandoni Military Air Rifle made from the above diagram. Two especially clever design features are shown here. First, note that the plunger, surrounded by several leather seal rings, can come right to the end to the pump, thus eliminating virtually all dead air space - an arrangement necessary to produce very high pressure in the gun's air reservoir. Second, note that the plunger head with its seal rings can be projected out of the pump body (as shown above) so that sealing oil may be applied directly to the leather seals. The seals may then be pulled into the pump body (as shown below) and a wrench applied to the lock nut- to precisely expand the seals to just the right seal and friction. Note that the pump rod is prevented from turning during this adjustment because its square shaft is held from turning by the square hole in the other end of the pump body. Photos by R. Beeman of museum copy pump by Ernie Cowan.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 16A - Original Girandoni repeating air rifle pouch with all accessories. Courtesy of Giancarlo Melano, on behalf of the Museo Nationale Storico d'Artiglieria, Turin, Italy. Operation of the Girandoni airgun system: The Girandoni military air rifle is a butt reservoir air rifle (a type known today as a Pre-Charged Pneumatic or PCP) with a rifled bore. This conical iron air reservoir serves to hold a supply of highly compressed air and to act as the rifle’s buttstock. An external tubular magazine, along the right side of the barrel was described as holding 20 lead balls which are gravity fed to a transverse loading bar at the breech end of the barrel. A flat spring running the length of the outside of the magazine holds the loading bar to the left. When the gun is held muzzle up and the left end of the loading bar is pushed by the shooter, the bar moves to the right, and a cavity within the bar receives a ball by gravity feed from the magazine. The ball is moved into firing position behind the barrel as the magazine spring is allowed to push the loading bar back to the left. Until very recently we did not have an understanding of the internal operation of a Girandoni air rifle. This lack of solid information led to considerable confusion and error. Thanks to the exhaustive work and study by Baker, Currie, Cowan, Keller, and Beeman, we now have a clear picture of the internal operation of this airgun. Presented here, for the first time, are color diagrams, by Geoffrey Baker, of the functioning of the ingenious lock and valve system of the Girandoni repeating air rifle. (Baker and Currie, 2002, 2006.)

Fig.19. Hammer pulled back to point where sear engages half-cock notch on tumbler. Second click. Hammer may be left in this “safe” position. In this mode the trigger should not be able to cause the hammer to fall and thus discharge the gun..

Figure 20. Hammer pulled back to engage sear in full cock notch. Third click. Gun is now ready to fire whenever trigger is pulled.

Figure 21. Trigger is pulled, allowing hammer to start forward and have tumbler wedge engage notch of striker latch. Wedge will push the striker assembly against air valve and start to release compressed air from reservoir

Figure 22. Tumbler wedge is beginning to push on the striker assembly which has started to force open the air valve in the reservoir. Pressurized air (indicated by dark blue) is beginning to be released from the air reservoir to force the ball up the barrel. The wedge will be forced out of the striker latch notch as the tumbler’s wedge rotates further, clockwise, to the rear.

Figure 23. Wedge is now rising out of the latch notch. Air valve is fully open. High pressure air is forcing the ball up the barrel. In the next stage the wedge will move back and slide out of the striker latch notch. The air pressure and the valve spring in the reservoir will then force the air valve shut. The hammer will then move forward and return to the rest position as shown in the first operation figure above.

Fig. 24. Girandoni Military Repeating Air Rifle. Close-up photos of the sear engaging the tumbler's cocking notches in a normally operating specimen of the Girandoni military air rifle in Europe. Upper image: sear engages the "safety" position of the half-cock. The deep lip of this notch prevents the sear from releasing if the trigger is pulled. Lower image: Sear engaging the full-cock position. Note that the tooth of the sear can easily be rotated out of the full-cock notch, thus discharging the gun, simply by pulling the trigger. (Again, note the much deeper, ledged half-cock notch at the left.) Photos of Girandoni military air rifle, serial number 1493, courtesy of Geoffrey Baker.

Fig. 25. Detail of first click when cocking. As the hammer turns the tumbler counter-clockwise during cocking, the striker latch (orange) is snapped up as the rear lip of the tumbler wedge passes the point at the tip of the lower arrow. Firearms lack a striker latch, therefore firearms do not produce a click at this point during cocking. (This, and all following diagrams, by Geoffery Baker.)

Fig. 26. Detail of second click when cocking. As the tumbler turns counter-clockwise, the sear (yellow) snaps into the normally deep half-cock notch at the tip of the lower arrow. The depth of this notch normally prevents the sear from coming out of the notch. This prevents the gun from discharging and serves as a “safe” position. (Early production of the Girandoni air rifles did not have a half-cock position.)

Fig. 27. Detail of third click. As the tumbler rotates counter-clockwise, the sear tip snaps into the full-cock notch at the point of the arrow. The gun will now discharge when pulling the trigger causes the sear to slip out of this shallow notch.

Figure 30. Detail of the striker assembly. (Upper diagram is a side view. Middle diagram is a top view.) When the air valve closes, propelled by high pressure air in the reservoir, it gives a sudden acceleration to the striker assembly. The striker latch guide screw limits the forward movement of the striker latch towards the barrel. The first operational figure above shows that this screw is supported at both ends to resist the beatings of the striker latch being driven forward. Its outer head is rounded for appearance and protection to the shooter’s finger. The striker latch guide screw does not have any adjustment role[4] Note that the striker latch is not symmetrical. Lower image shows actual parts from the Beeman Girandoni. ©2005, Robert David Beeman After moving a ball into firing position, the gun is cocked by pulling back on a hammer-like cocking lever. Moving the cocking lever back causes an internal tumbler on the inner end of the cocking lever (hammer) to force the mainspring down into a compressed position. The cocking lever is held to the rear, against the pressure of the mainspring, by the half cock or full cock sear notches. When the trigger is pulled and the tumbler is in the full cock position, the rearmost section of the trigger forces the sear out of the full cock notch. The released force of the mainspring forces the tumbler to rotate, bringing the tip of a wedge shaped part on the tumbler into the notch of the striker latch. The force of the mainspring is converted into a straight line motion as the wedge pushes the striker latch and thus the attached striker pin against the forward end of the air reservoir’s valve. The tip of the striker pin forces open the valve and releases a short blast of compressed air to force the ball up and out of the barrel. The wedge then slips past the striker latch and the air valve spring, aided by air pressure in the reservoir, forces the air valve shut and returns the striker assembly back into its resting position. Movement of the wedge is reversed during re-cocking, depressing the striker latch and allowing the wedge to pass without disturbing the striker assembly and air valve. This all can be repeated so rapidly that all 22 balls could be fired in less than a minute.

Fig. 31. Lead balls for the museum copy. Right: unfired ball. Left: Ball fired by the author into soft material from a Cowan museum copy of the Beeman Girandoni, 750 psi air pressure. This may be one of the first balls fired from a military Girandoni for the last century or two! Discharge sound was lower than a firearm of equal power, but fairly loud. Beeman collection and photo.©2005, Robert David Beeman The Girandoni lock system is a quite sophisticated, well-designed timed release design, The repeating mechanism reveals the genius of its design by its efficiency and simplicity. Baker and Currie (2002) make the very interesting observation that there wasn’t another conventional military shoulder arm comparable to the firepower of the Girandoni repeating air rifle until the 1860 Spencer repeating firearm rifle of the American Civil War. However, the Spencer had only a seven shot magazine and had to be reloaded frequently by the rather clumsy Blakeslee loader. The Girandoni military air rifle had a gravity feed ball magazine listed at 20 rounds. Each Girandoni-bearing military shooter was issued two extra air cylinders and four very efficient speedloader tubes, each containing twenty additional balls. A fully loaded Girandoni kit had eighty more of those large caliber balls ready for rapid action! In typical military use, discharged, or partially discharged, air cylinders would be exchanged for fresh full ones by runners going back and forth to stationary wheel pumps or special two axle wagons designed to carry up to 1000 pre-charged air cylinders, both positioned behind the combat lines. Certainly the soldiers were not going to fully pump up their three cylinders in regular use as this would require about 4500 strokes with the hand pump! Even a single cylinder could have taken a half hour of hard pumping action! But the long slim pump, designed almost without dead space would be useful in “topping off” high pressure in partially expended cylinders. The outstanding study of the history of the Girandoni Military Repeater Air Rifle by Walter Hummelberger and Leo Scharer (1964) reveals that the success of the Girandoni air rifle in warfare has been a mixed matter. About 1780, the Austrian military authorities, driven by Emperor Joseph’s personal involvement and great enthusiasm for the Girandoni airguns, had secretly begun the development of the so-called Austrian Military Model 1780 Repeating Air Rifle. By August 24, 1787, when Istanbul declared war against Russia, some air rifles and pumps were the only things that were ready for war. It was realized from the beginning that it might not be practical to provide all the compressed air for these guns from little individual hand pumps. So Girandoni developed a wheeled pump to fill massed concentrations of the removable air bottles of the guns. Originally, it was planned to have one such wheeled air machine for each five air rifles, plus the long hand pumps, but only two of the wheeled pumps actually were produced[5]. Later, it was decided to issue a hand pump to only every other soldier, underlining that the soldiers mainly were expected to depend on pre-charged air bottles brought to them by runners. Girandoni developed a two axle wheeled wagon, or transporter, to safely carry up to 1000 of the pre-charged air bottles. The conical butt reservoir may seem primitive, but actually this shape is extremely functional. One of the most annoying features of many airguns with buttstock shaped air reservoirs in the Beeman collection is the difficulty of getting the vertical axis of the buttstock to line up with the vertical axis of the receiver. A conical butt reservoir is round in cross section and thus there is no alignment problem; one only need screw it onto the receiver until it is snug. Thus the flat ring gasket between the receiver and reservoir, made of cow horn, can be of any reasonable thickness, regardless of tolerances, wear, oil swelling, or humidity. The reservoir shape has little ergonomic disadvantage as recoil is negligible.

The

steps in making a conical butt reservoir are shown in the

illustrations. Riveting the edges of the rolled edges is a

somewhat difficult operation, even today. However, the

real trick is brazing the rolled edges and the base cup.

At first, standard brazing technique was used, but this just

would not result in a leak proof reservoir. Finally, the

answer was found in information about 19th century steam tank

fabrication. The old, but very effective, technique was to

heat the riveted reservoir red hot and submerge it in molten

brazing metal! Learning this also answered something that

had puzzled us: why were the Girandoni reservoirs coated,

inside and out, with copper like metal? This inner coating also

provided a rust proofing against moisture resulting from the

expansion of compressed air. Making the reservoirs, in an

authentic manner, will be one of the major challenges to those

who would attempt to replicate these guns today. Thus, the Girandoni air rifle in combat required persons highly trained in its use and supported by wheeled air pumps and wagons of pre-charged air bottles. These air guns easily were put of service and needed constant and expert tending. A Girandoni air rifle was predestined to give inexperienced users trouble and charging with individual hand pumps was punishing to the user. The dependability of the gun for lethal combat, under field conditions, especially without the backup of dozens of other airguns, was not high. Because of the sophisticated nature of the flat mainspring and the timed release mechanism, Baker and Currie (2002, 2006) suggest that the Girandoni system is capable of much greater power than air rifles of less advanced design. As of May 2003 they were only willing to indicate that this system could project a lead ball, of about one-half inch diameter, of about 210 grains to a muzzle velocity of at least 500 fps for about 117 ft. lbs. of muzzle energy. Colin Currie reported (personal communication May 18, 2003) that the Royal Armories of Leeds, England recently charged the Heiberger .433 caliber air rifle, a formerly single shot air rifle made about 1750 but converted to a 23 shot Girandoni-style repeating system[6], apparently in the early to mid-1800s, to about 800 lbs/sq. inch and achieved a muzzle velocity of over 900 fps with balls of 120.4 grains for a muzzle energy of 217 ft. lbs. He reported that 1500 strokes were needed to pump up the Heiberger‘s buttstock reservoir to operating pressure after 20 shots had been fired from one charging/loading. Larry Hannusch (personal communication, Nov. 27, 2002) reported that he has fired his own large bore Girandoni-system rifle (by Lowentz) producing 200 ft lbs. muzzle energy at 750 psi pressure, but that a muzzle energy of up to 150 ft. lbs. would be more typical at conservative pressures. Many references to the Girandoni air rifles mention lethal combat ranges of 125 to 150 yards and some extend that range considerably. Currie and Baker also suggest that the Girandoni system could operate well at pressures well above 1000 psi, perhaps to double of that, and that they feel that the working pressure as supplied by special pumps, and thus the potential power, of the original guns was far higher than the figures normally quoted. Keller and Cowan (personal communications 9 November 2004 and 14 February 2005) think that the original air reservoir pressures topped at about 800 psi. The potential muzzle energy will be more accurately determined from tests now underway with exact museum copies of these guns. The power could be in the .38 Special area of modern firearms, or even, as probably overstated by Fred Baer (1973) into the range of the .45 ACP cartridge, famous in pistols and submachine guns favored by police, gangsters, and the military for several wars of the 20th century. In any case, that heavy lead ball, fired from a Girandoni-system airgun, could be a very lethal object! High air reservoir pressures, translating into high power, could be an advantage in battle where charged cylinders were being shunted to and from the shooters. However, such pressures and volumes of air per shot for such large bore airguns present such a fearful appetite for compressed air that modern shooters of pre-charged pneumatic rifles resort to SCUBA tanks and motorized pumps for charging. The power levels discussed above were very potent for the period. However, foot pounds of energy do not tell the whole story. Few hunters today would venture after big game with the energy levels of the old big bore airguns or flintlocks, but those big lead balls, about a half-inch in diameter, have a special effect – as does a deadly arrow with “only” fifty foot pounds of striking energy. One has to respect a gun capable of flattening a huge lead ball against a distant steel plate, especially when a typical Girandoni system gun could deliver about 20 of those heavy missiles within the minute and another 80 rather suddenly! The simple great inertia and the large wound channel of those big lead balls also makes them far more dangerous than paper figures would suggest. Side Note on the Beeman Girandoni military air rifle: We purchased the illustrated specimen (the "Beeman Girandoni") from the private collection of an American antique gun dealer about 1975 without any provenance. The master gun reproduction maker/historians, Ernie Cowan and Richard Keller, have made just four ultra precise museum copies of this specimen. They are extremely impressed with the excellent craftsmanship and engineering - all parts are arsenal marked as matching and very well fitted. The air reservoir bears a brazing metal coating - a feature of the Girandoni produced airguns. Cowan and Keller, directly studying the actual gun, indicates that not only are they convinced that this was one of the military models of the Girandoni military air rifles, made somewhere in the middle of the actual Girandoni production (construction details, such as the presence of a half cock, would place it about 1798), but that it probably was an actual combat gun which was illegally possessed outside of the military circle. This is evidenced by the apparent removal of the serial number on what clearly is an authentic Girandoni military model. Cowan indicates that the receiver profile seems to be somewhat lower and thinner in the locations where the serial number would be expected and the front of the air reservoir end cap, where another serial number would be expected, appears to have been filed shorter. (Close examination shows that the front of this tapered brass piece falls a little short of the diameter of the adjoining receiver.) The true military status of this wonderful specimen, as revealed by factory markings and exact measurements, was confirmed by the British airgun historians, Currie and Baker. They have been producing a series of books detailing the construction of famous historical types of airguns. Their conclusion is that this airgun is an authentic military production specimen diverted to the civilian market. Baer (1973) indicates that Girandoni was accused of diverting some specimens to the more profitable civilian market. Some specifications: Unloaded weight = 9.2 lbs., loaded w/ 21 lead balls = 9.6 lbs. Weight of empty air reservoir assembly = 3.0 lbs. The barrel is wrought iron. Rifling is excellent, and relatively shallow (about 5 thousands of an inch), commensurate with high efficiency in an airgun.). The air valve consists of three stacked pieces of hard leather, cut to a 60 degree slope to match the slope of the brass valve seat. The front sight is brass or bronze. Finish of protected iron surfaces is a dull dark, hot bluing. MYTHS ABOUT THE GIRANDONI AIRGUNS There are several oft-repeated tales about Girandoni system airguns which we now know to be fanciful. Some historical accounts simply are not true or they may contain comments that are not true. First, One of the most common myths is that Napoleon ordered the hanging of anyone in possession of an airgun. The late Arne Hoff, famed arms historian and curator of the Royal Danish Arsenal, and others, have commented that this story, told as the “eye witness” war experience of French General Mortier, has now been quite thoroughly refuted (Baer, 1973). This story may have grown from the fact that many towns, fearing these unfamiliar, terrifying guns - even without any negative incidents, banned airguns. A death penalty was common for many offenses, so it is possible that some airgunners were put to death. One story relates that the city fathers had a gunsmith, who knew how to make airguns, blinded! Second, apparently there never was any incident of the air rifles being used against Napoleon’s troops. Third, it is often related that these guns were silent. A number of city, and other governmental decrees of the 1800s, made the guns illegal, often largely on this basis. I can state from personal firing of one of Cowan's fully-charged museum copy of the Girandoni military air rifle that the discharge sound is quite audible, though by no means as loud as a similar large bore flintlock firearm and evidently much less loud than the report of many antique or modern pre-charged pneumatic rifle.. However, the fact that the guns discharge without smoke or muzzle/pan flash does make locating the position of someone firing such a gun much more difficult. (Modern note: Powerful, modern, silenced, 9mm PCP airguns are being used by U.S. Seals in Iraq to snipe at insurgents. Firing an M-16 at dawn or dusk could attract a lot of return fire to the flash point.) A GIRANDONI SYSTEM "HYBRID" This combination of a Girandoni system and an older Heiberger single shot air rifle is especially interesting.

Upper images -RHS and top views of the Heiberger/Girandoni Combination. Middle image: Barrel and repeater assembly removed from Heiberger converted airgun, rear view. Note that the decorative lines of the second rear sight, loading block retainer bolt heads (grooved rectangular units on top of each end of the loading block), plain finish, magazine spring, magazine length, and magazine hatch handle are exact Girandoni styling. Also note the brass bore liner which reduces the volume of the transfer chamber (the round profile rear extension) between the reservoir valve and the lead ball in firing position. This bore liner would also jet the air towards the ball and serve to reduce rust due to adiabatic condensation. The round profile extension (steel?) behind the wrought iron barrel/loading bar assembly surely is an addition specifically made to fit it to the Heiberger action - no such extensions are known in other Girandoni-system airguns and the profile, length, and threads exactly fit the Heiberger action. (This extension has rifling continuous with the rifling in front of the loading block - this would be the result of relining and rerifling the entire barrel or of "freshening" the original rifling.) (BTW: Owner David Swan, in England, assures me that the Girandoni-system addition is NOT marked as to maker - the report in Airgun Hobby magazine that it was marked with the Contriner name was an editing error.) David uses 11mm (.433") lead balls, which may be a loose fit in the bore.. The barrel is rifled with 12 grooves with a right hand twist, with 1 turn in 25.5 inches, a much faster turn than found in flintlock firearms of the period. The rifling twist of this arm is a little faster than the 26.25 inch twist of the original Girandoni military air rifle barrels, evidently an adaptation to the higher velocity of the slightly smaller projectile of this gun. The ID of the magazine tube is 11.9mm (0.470") and the loading block ball recess is 12.1 mm (0.476") in diameter; measurements consistent with these parts having been acquired from a standard 11.75 mm Girandoni military air rifle..

Lower picture: Lead balls, .11 mm (433") caliber, before and after being fired at a steel plate from the converted Heiberger repeating air rifle in 2002. Note lack of any rifling marks. Fig. 32. Single Shot Air Rifle by C. Heiberger of Vienna, made ca. 1750-1760, converted to Girandoni system repeater action, apparently using the barrel, magazine, and action from a Girandoni-system air rifle. Conversion ca. 1815-40. This conversion could have been rather easily accomplished by simply adding a short barrel extension to a barrel assembly, with attached loading block, magazine tube, and even sights, from a disabled Girandoni-system airgun into the Heiberger receiver. Note that the Heiberger conversion has two rear sights: an original one on the receiver and a Girandoni style one which came with the added barrel/repeater assembly (that forward Girandoni sight is too low to be seen by the shooter over the original rear sight!). This 23 shot repeater has a standard V-shaped internal mainspring. The nature and size of the external cocking lever ("hammer") indicates that the mainspring was very powerful. The round section buttstock air reservoir may also be a later Girandoni-system item. Fires very loudly and flattens its discharged balls very impressively against a distant steel plate. The high sound may be a side effect of loose ball fit. Probably a "one-off" item, of considerable power and great firepower, without decoration but in excellent condition. While understandably lacking many design features of the Girandoni military repeater, it functions well and would have been a fearsome weapon. The Heiberger does have at least a couple of superior features not found in the later regular Girandoni air rifle design: an air bypass lever (on the left lock plate) and a far stronger fused two-part receiver body of heavy cast bronze both top and bottom. This particular gun may be the only such conversion ever made; no other such specimens are known. No case or pump are known for this gun. Of course, because it was built as a hunting arm, rather than as a military arm, no speed loaders ("spare magazines") are known. The workmanship of the conversion is of a considerably lower quality than the original Heiberger gun. It does not appear to have been done by a highly skilled gunsmith. This Heiberger/Girandoni-system conversion gun had been stored as No. 425 in the Salm-Reifferscheid Armory, Schloss Dyck (Dyck Castle, near Düsseldorf, Germany) until 1992 and apparently has never left Europe. Courtesy David Swan collection, photos by David Swan. GIRANDONI REPEATING AIR PISTOL

Figure 33. Girandoni Repeating Air Pistol - About 1800. Approx. 9 mm. This superbly made, gold-plated, silver inlaid, deeply engraved pistol on the exact Girandoni system clearly was made for an important, perhaps royal, user. It has been suggested that this pistol was made by the master airgunsmith Joseph Contriner for Girandoni, but he signed his work "JC" - the lock on this gun clearly shows a "JG". Bartholomäus Girandoni did have sons named Bartholomäus Jr. and Johann Girandoni. This suggests, as was previously not known, that Johann, described as especially talented and trained by his father in "technical skills", may have been involved in the production of the Girandoni repeating airguns - perhaps in the Contriner shop in Vienna, after his father's death in 1799. Note that the barrel is signed "Girandony" - a known spelling variation of the family name that may have been used by Johann Girandoni. This very specimen is shown on pg. 93 of Wolff (1958). Courtesy of Beeman collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

GIRANDONI SYSTEM AND GIRANDONI STYLE AIRGUNS Notice, even on the single shot guns, the flask shaped air reservoirs and the diagnostic "little notch" which aligns the lock plate in the receiver body. Research is only beginning on these specimens. Additional information, input, and specimens are all much needed and solicited for this research. This photo series is only intended to give a general impression of some of the variety of these guns.

Fig. 34. Girandoni style single shot air rifle by Hans Ascha of Vienna, ca. 1818. Courtesy of Beeman Collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

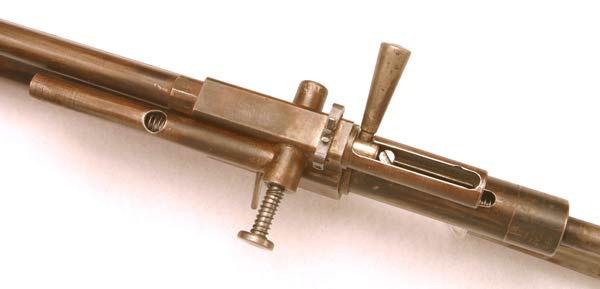

Fig. 35. Girandoni-system repeating air rifle by Joseph Lowentz (Lowenz) in Vienna, ca. 1810. This airgun has a bore size about 0.464" and a 17 shot gravity fed magazine with an inside diameter about 0.470". Note the auction tag giving the professional antique gun appraiser's combined value of 1000 to 1200 British Pounds for the combined lot number 164 ot the three airguns shown in the fourth image above. (Dec. 2004: 1 BP= US$1.90). Courtesy of Beeman collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig.36. Girandoni style single shot airgun, for ball or shot, signed by Lowentz. Almost exact same styling as the Lowentz repeating air rifle above. This specimen shown on pg. 94 of Wolff (1958). Courtesy of Beeman Collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 37. Girandoni-system repeating air rifle by Joseph Contriner in Vienna, ca. 1810. Terrible image of the one of the finest Girandoni-system air guns known. Photo is copied from image of this specimen on pg. 93 of Wolff (1958) because gun is being professionally restored by Ernest Cowan and not available for photos. Gold plated, silver inlaid, deeply engraved- perhaps even more elegant than the Girandoni air pistol shown above. Magazine capacity of about 16 balls (est.). Courtesy of Beeman Collection.

Fig. 38.Inside view of lock from above Contriner air rifle. Note the V-shaped mainspring! Courtesy of Beeman Collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 39. Girandoni-style single shot air rifle or air shotgun signed by Stirtia of Vienna, ca. 1820. Unusually long .42 caliber smoothbore iron barrel tightly wrapped with attractive fiber braiding. Courtesy of Beeman Collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 40. Girandoni-style single shot airgun or air shotgun by unknown maker. Probably ca. 1830. Courtesy of Beeman collection.©2005, Robert David Beeman

A VERY SPECIAL GIRANDONI SYSTEM AIR RIFLE Made in the 1940s during WW2, this gun doesn't look like a Girandoni, but examination shows that it clearly was built by someone familiar with the Girandoni repeating airgun system. Purchased in Europe, the story is that this gun was built somewhere in occupied Europe by a partisan bicycle maker during the Nazi occupation in WW2 . (Originally we suspected that the maker was in Austria but an Austrian friend pointed out that there really wasn't any resistance movement in Austria - most Austrians still considered Germany and Austria as a single unit, as it had been in the past, and actually welcomed the Nazi troops when they occupied the country, virtually without force.) The repeating magazine is spring fed and on the left side of the barrel, for the convenient use of a right handed shooter. The gun was charged with the accompanying bicycle type pump. Smoothbore, as would be expected, but firing a 11 3/4 mm lead ball (.464" caliber) (the very same caliber as the original Girandoni Austrian military repeating air rifles!), this would have been a fearsome weapon against sentries, drivers, military leaders, etc. at ranges up to perhaps 100 yards. To a freedom fighter, the lower discharge sound and the lack of flash or smoke would have been huge values. And it did not need powder, primers, or bullets - only easily cast lead or soft-metal balls! The builder surely drew his inspiration from a museum, or even just a book, which displayed a Girandoni system airgun. The excellent quality reflects the experience of a perfectionist bicycle maker with considerable time on his hands - consistent with such a craftsman in an occupied area. Note that this gun has a spring fed magazine, rather than the gravity fed magazine of the original Girandoni military air rifle. While a gravity feed mechanism might be simpler, and even more dependable, the spring fed magazine has great advantages for the purposes of this gun. It is more suited for operation from a vehicle or firing slot where it would be impractical to tip up the rifle for loading and it allows firing with minimal motion at the firing point - very important to a sniper. Why would a modern sniper want a functional version of an ancient airgun when automatic weapons were as close as the first German soldier that could be waylaid? The answer dramatically comes from the above notes and the fact that an American maker is now doing a small, but excellent, business supplying coalition troops in the near East with high power 9mm repeating PCP air rifles, complete with silencers and nightsights. Unlike a firearm, such a weapon, without sound, flash, or smoke, does not attract return fire - esp. in reduced light situations - the deadly projectile just seems to come from no-where! Basic specs: A husky 12.2 lbs., 45" overall, glare-free, w/ almost camo anodized type finish.

Fig.41. "Partisan Airgun" - fearsome anti-Nazi weapon clearly based on the Girandoni repeating airgun system. Courtesy of Beeman Collection.©2004, Robert David Beeman THE PINNACLE OF AUSTRIAN AIR GUNS: (Click on picture for a larger view!) Fig. 42. Austrian air rifle built for an emperor? A truly elegant double barreled rifle - left barrel is a percussion, muzzle-loading firearm. The right barrel is a breech loading, butt-reservoir air rifle - about .40 caliber - Pushing forward on a lever in the trigger guard causes an invisible breech block to rise up out of the top of the receiver for easy, fast loading. Deeply inlaid gold letters include numerals on the left side let you set a four step power selection lever for bunnies to bear! Extremely deep engraving, gold inlays, elegant calf-skin covered butt reservoir- ca. 1850-60? Photo by R. Valentine Atkinson. Courtesy of Beeman Collection. What may be the pinnacle of evolutionary development of the Austrian Girandoni system is shown in the accompanying picture of a 19th century Austrian side-by-side double-barrel air/percussion combination. The key feature of the genius of the Girandoni system, a sliding breech block with a ball socket, has here evolved into a concealed, vertically moving breech block with a similar ball socket. The firepower of the long magazine has been replaced with the combination of firepower and dependability of a double-barrel gun with two completely different power sources. The round-bottom, conical flask air reservoir has evolved into a leather covered air container shaped like a modern long arm buttstock. Do Lukens Air Rifles show Girandoni Styling ? I have commented in the Lukens airgun paper on this website, that, as previously discussed between myself and the late Henry Stewart, that the “shape and style” of the Lukens airgun receivers seemed to be similar to the receivers on Girandoni-style Austrian butt reservoir air rifles in the Beeman collection. Thus, I was obliged to again compare the receivers of Girandoni style repeating airguns with those of Lukens single shot air rifles. Although there is superficial external similarity due to being rounded, as is common, and having the air reservoir connection, barrel base, and lock in similar locations, as would be dictated by function, the receivers, and also the air reservoirs, of the two lines of airguns are very different. Internally, and in all the lock areas, the Girandoni airguns and the Lukens airguns are completely different. The Lukens and Girandoni receivers are vastly different. The Girandoni receiver basically is just a single brass top piece, cast from top to bottom, with the lower area of the receiver being just the trigger guard and an extension of the wooden stock. A simple, rather diagnostic, notch along the lower, right edge of the brass casting holds the rear tip of the lock plate, simplifying assembly. The Lukens/Kunz air rifles have a two receiver piece brass receiver, cast from side to side and brazed along the center line - the solid metal receiver completely enclosing the central area of the gun, top and bottom. In the Lukens the air transfer tube is brazed into place when the two side shells are joined. This is detailed in the paper on the Lukens gun itself. In the Girandoni the air transfer channel is a tunnel drilled and filed or cast in place. When Stewart, and later I, made the remark about similarity of Girandoni and Lukens styling we were not aware of the complete contrast of the mechanisms and structure. We were only referring to superficial cosmetic appearance and the presence of a butt reservoir. Similar cosmetic styling, but certainly not structure, of the receiver was found at least as far back as a single shot air rifle by C. Heiberger, a Luftbüchsenmacher (airgun maker) of Vienna, about 1750. And while the Lukens butt reservoir is not very much like the Girandoni reservoir, it is similar to butt reservoirs found on external lock air rifles that go back two centuries. Conclusion: There appears to be not the slightest indication that the style or design of either gun was influenced by the style or design of the other. The styling of each can be traced as separate back to at least the mid-1700s.

We VERY MUCH welcome information on other Girandoni system airguns and are always on the market to buy additional specimens for inclusion in our upcoming book which finally will tie the existing specimens together into a permanent legacy for this gun-making genius - a collection which is destined to be maintained as a unit in an appropriate international arms museum - rather than being sold and thus scattered into obscurity over the globe. SELECTED REFERENCES AND LITERATURE CITED See also the reference lists for this website's two Lewis Airgun chapters: Lewis Assault Rifle and Lewis Airgun - preliminary study.. Baer, Fred 1955. The Gun That Scared Napoleon. GUNS, March, 1955. Baer, Fred. 1973. Napoleon Was Not Afraid of It In: Arms and Armor Annual, Ed. By Robert Held, Digest Books, Northfield, Illinois. Baker, Geoffrey and Colin Currie, 2002. The Construction and Operation of the Air Gun. Vol. 1. The Austrian Army Repeating Air Rifle. 64 pp. www.gunbooks.co.uk. This book, one of the most important works ever on the Girandoni air rifle, primarily is detailed drawings of the gun and its parts. It was revised and corrected to include new work by Baker, Currie, Cowan, Keller, and Beeman as a second edition of 102 pages published in 2006. The second edition of this stellar book is absolutely essential to anyone interested in the Girandoni airguns. A similar book detailing the construction of aircanes has also been produced by this industrious and exacting pair.) Beeman, Robert. 2006. Meriwether Lewis's Wonder Weapon. We Proceeded On, official journal of the Lewis and Clark Heritage Trail Association. May 2006, p.29-34. Blackmore, Howard 1965. Guns and Rifles of the World. Viking Press, New York. Redwood Press Limited, Trowbridge & London.134 pp. Brown, Shaun 2002. Samuel Staudenmayer, Gunsmith, Cockspur Street, London. Arms Collecting 40(3);90-93. Brutsche, Helmut. 1966. Die Geschichtliche ent Wicklung der Windbüchsen. Deutsches Waffen-Journal, May, 1966. pp.71-75.(Also published in International Arms Review, Vol.1.) Demmin, Auguste 1893. Die

Kriegswaffen in ihren geschichtlichen Entwicklungen , p. 976,

Leipzig. Gaylord, Tom 1997. The Girandoni Air Rifle. Airgun Revue 1: 10-11. Hoff, Arne, 1977. Windbüchsen und andere Druckluftwaffen. 105 pp.. Parey, Berlin. Hummelberger, Walter and Leo Scharer. 1963. Eine Repetier-Windpistole. Wiener Geschichtsblätter, 204 sqq.. Hummelberger, Walter and Leo Scharer. 1964. Die österreichishce Militär-Repetierwindbüchse und ihr Erfinder Bartholomäus Girandoni. Part 1: Pp. 81-95.1965: Part 2:24-53. Zeitschrift fur Historische Waffenkunde. Deutscher Kunstverlag, München, Berlin. Konwiarz, Christian 1983. Test Firing a 150 Year Old Air Rifle. The Gun Report, August 1983:14-20. Munson, H. Lee. 1992. The Mortimer Gunmakers- 1753-1923.Andrew Mowbray Inc, Lincoln, Rhode Island.. 320 pp. Rothenbücher, C. 1816. Über den Brand der Gewehre. Zeitschrift für das Forst und Jagdwessen im Königreich Bayern 4: 40-42. Saunders, Tim. 2003. Sniper's Delight. Airgun World pp.72-3. (Heiberger-Girandoni conversion) Schäfer, Otto, 1961. Die Windbüchsen im Museum Kranichstein. Deutsche Jäger Zeitung.. January 1961:No. 20 and 21.. Melsungen, Germany. Stumpf, Manfred 1960 Waffen Almanach. Fachverlag Dr. N. Stoytscheff, Darmstadt, Germany. 256 pp. (See esp. the 1766 Windbüchsen warning on p. 208.) Train, J.K. 1844. Die Niederjagd in allen ihren Verzweigungen vol. 1:28-32. Ulm, Germany. Støckel, Johan F., 1978-82. Revision edited by Eugene Heer: Heer der Neue Støckel. Internationales Lexikon der Büchsenmacher, Feurwaffenfabrikanten und Armbrustmacher von 1400-1900. 2287 pp. Journal-Verlang, Schwend GmbH, Schwäbish Hall, Germany. Wolff, Eldon 1958, Air Guns. 198 pp. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in History 1. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Wolff, Eldon 1963, Air Gun Batteries. 28 pp. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in History 5. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. [1] “Rapping” is the quick snapping of the cylinder down against the pump to top off the air that can be entered by regular pumping. Rapping in air vs. pushing it in can be compared to hammering in a nail vs. pushing it in with a hammer. For many years I have been "rapping" higher pressures into Yewha and other pneumatic guns than could have been predicted on the basis of my tenth-of-a-ton weight. (Both Barnes and Gaylord, have since reported -via personal communication of October 20, 1999 - that such "rapping" can indeed produce air storage pressures in some airguns greater than would be predicted from the body weight of the shooter. The weight of the shooter may be almost irrelevant in determining the air pressure that he can produce.). Recent tests by Beeman, Cowan, and Currie indicate that such "rapping" is not possible with the Girandoni airguns. [2] An intriguing feature of these pumps is their ingenious design: the upper end of the pump shaft is square in cross section. After pushing the pump head out for cleaning and oiling the seals would be pulled just into the pump’s bore. Then the square shaft passing through a square guide cap would hold the shaft still as the threaded pump seal nut was turned to expand the seals, thus providing perfect fit and tightness. [3] Geoffrey Baker (personal communication, 10 November 2004) commented: The shorter larger diameter pump would not reach as high a pressure as the longer thinner one. The air vent has lost volume which is not much of a problem at lower pressures .For high pressure it is essential to have as little lost or “dead” volume as possible. Girandoni was a genius. He very cleverly got around this problem by continuing the pump tube right up to the end. Air cane pumps are similar to the shorter one and the air vent is relatively large. Modern pumps like the Slim Jim variety used by the now defunct Brocock Company had a tiny air vent but they are designed to pump to much higher pressures than the aircane ones. (The short. thick pump is the type known from most specimens of antique airguns.) [4]. The impact of firing seems to loosen this screw. [5] Girandoni reported that the wheeled pumps actually were a bit slower than the long hand pumps, but even though the filling of an air bottle would require the same amount of energy input from a wheeled pump as from a hand pump, the wheeled pump must have been enormously easier to use. It is staggering to think of the amount of manpower that would have necessary to keep those transporter wagons full of hundreds of fully charged air bottles, plus shunting them to the shooters. This alone could have been a key reason for the decline of the airgun as a regular military weapon. [6] Almost surely, only one such conversion has ever been made. The Heiberger/Girandoni conversion gun had been stored in Schloss Dyck (Dyck Castle, near Düsseldorf, Germany) until 1992 and apparently has never left Europe. There is no indication that a Heiberger airgun, listed by Wolff (1958) as being in the Mack collection in America in 1958, ever was anything but an original single shot airgun. It is the only Heiberger known by the author to have been in the Americas. [1] Dr. Robert Beeman is a Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation member, Professor Emeritus at San Francisco State University, founder of Beeman Precision Airguns, publisher of Airgun Journal and Airgun News, author of many airgun publications and bulletins, airgun designer, airgunsmith, senior author of the Blue Book of Airguns series, airgun expert witness, airgun consultant, and airgun collector and historian. |